PhD Thesis: The Ecological Body ~ extracts

Transition and Position

May the road rise to meet you

May the wind be always at your back May the sun shine warm upon your face May the rain fall softly on your fields Until we meet again May God hold you in the hollow of his hand Traditional Gaelic Blessing Movement is the basic default, with ‘stillness’ or ‘stopping’ as pauses in the line of movement. In absolute terms, there is no such thing as a fixed ‘position’ because there is always movement. However, within a comparative framework, the kinaesthetic emphasis in Western daily life is on one’s position, on goals and on structure rather than paying attention to transition: that is to process, to the journey or to the spaces between activities. To redress the balance, I point to transition even though position is, itself, transition. Taking ‘change’ as home ground suggests an approach to life which acknowledges the potential for transformation.

Transition/position gives a structure for exploring ‘travelling and staying’ as different modes of being. Motivations, desires and perceptions of place change according to which mode one is operating within. As a result, different values can often lead to misunderstandings between ‘dwellers’ and ‘travellers’, for example, between indigenous peoples and tourists. At a broader level, these preferences connect with inter-cultural issues of territory, invasion, colonialism, bioregionalism and the flux of emigration and immigration. The structure of transition/position in movement may help us to perceive cultural attitudes which we may not have challenged within ourselves, for example qualities of directness or diplomacy. Applying cultural lenses to different movement dynamics, such as active/passive, transition/position, proportions and point, line and angle may reveal the somatic heritage of other habitual cultural mechanisms. By becoming aware of how our behaviour and societal practices are still influenced by these incorporated patterns, we may eventually create the conceptual and physical ‘gap’, so that we have the capacity to adapt and to be flexible enough to create a third possibility, between going and staying, which seems necessary for a fluid intercultural society. This I see as a co-creation of a complex environment which values diversity, proportionate activity and personal transience. Strata.

The Green Road site with the derelict cottage provided a situation with a road and a dwelling, which offered the potential for exploring transition and position When a participant chose to stay and move near the dwelling, rather than walk along the path, they became aware of how their practice of ‘staying’ was influencing their movement, their personal associations, their community and their view of the past.. During social time, I encouraged participants to be aware of how the particular movement dynamic they were working with that day influenced their daily life movement and communication: to notice their transitions between situations, or to feel when they were initiating contact or choosing to stay alone I myself worked from an awareness of all four dynamics during the workshop sessions and during the participants’ ‘free time’ and social events, as a way of immersing myself in the practice I was proposing.

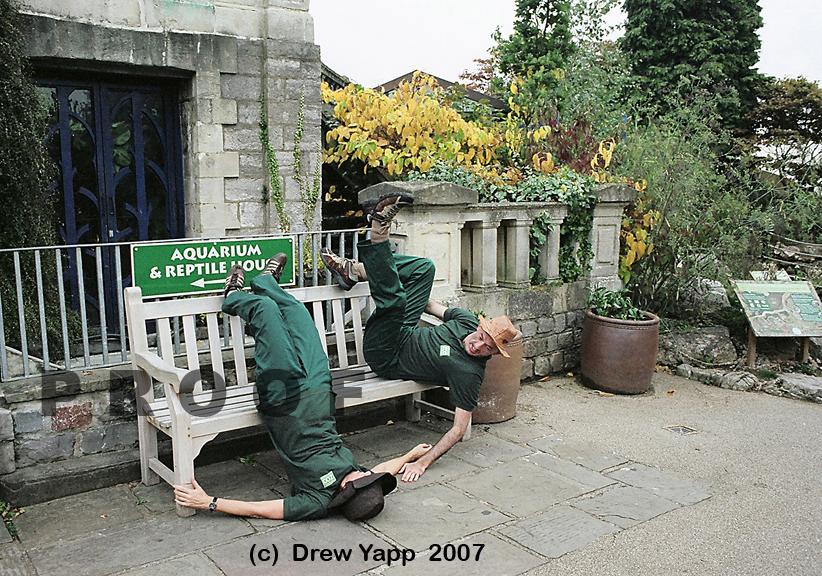

Being in Between (Photos: Drew Yapp) Transition /position offered a way of exploring the difference between going and staying. Should I stay or should I go? Do I leave or do I put down roots? These two modes of movement have different priorities and offer different perceptions of the world. I was interested in articulating these differences within the performance. The performers looked at the site from the viewpoint of going and staying: the pathways and the enclosures; the cyclical rhythm of the day, filling and emptying with visitors; the fact that most of the animals had been imported into this foreign environment and climate. They practised different pathways and rhythms of moving through the site and also finding positions and places to stay. They worked with prepositions which also offered embodied ways of relating differently to the same environment e.g. in the café, through the café, opposite the café. Import, export, genetic compatibility, movement patterns in the wild in relation to movement patterns in enclosures were all areas that we spoke about as a result of practising transition and position.

Movement Studies

I introduced the theme of transition/position and invited responses from each of the artists. Jenna Kumiega produced a poem, recorded texts as voiceover and sent me some questions on the theme of transition/position to respond to through movement; Dave West decided to work with moving images and stills to reflect the theme of transition/position. Eleanor Davis, a violinist, collaborated with me. I did not want her to ‘accompany’ me in any traditional sense but for her to work from her interpretation of transition/position in her own playing and for us to dialogue from the material we developed. Each of these creative elements arose as a conscious response to the proposed dynamic, both in terms of content but also in terms of technique, i.e. how they were actually produced or the attitude with which they were produced. For example, the musician applied transition/position to an exploration of how she physically held and played the violin. (Photo: Dave West) By being rigorous in my exploration of an extrinsically knowable dynamic e.g. transition/ position, I stood more chance of avoiding the production of movement clichés and assumptions, in terms of my fixed ideas of my particular characteristics than if I had decided to explore the intrinsically meaning-laden themes of ‘arriving and leaving’ or ‘being at home’. This served to extend and give precision to my movement range. The entire process was a way of releasing a fixed and deterministic notion of self by studying my movement as one dynamic within a field of environmental dynamics. Borders of Humility and Humiliation

Second, a fixed score and spontaneously improvised material existed in my own two primary styles of performance training. These were a Grotowski-based acting style, which demanded the fixed and rigorous scoring of originally improvised material (position), and environmental movement, developed from my studies in Amerta Movement, which involved spontaneous design and composition through improvised movement in relation to changing circumstances (transition), thus developing an involved and anticipatory awareness of patterns. This apparent polarity would, in fact, inform the aesthetics of the piece. How to involve the audience within the ecology of the performance?

I decided that, in relation to the movement dynamics that I had explored, the audience needed to be an active part of the changing movement and to experience point, line and angle, proportions and position and transition through their own audience-movement. Transition and Position in Java

"I began to notice the stillness and motion in the nature around us, the bamboo rustling as a gust of wind came through or the stillness of a stone and my own movement in dialogue with those sensations. I noticed how my choices could be influenced by someone else moving past me or by someone that I wanted to find across the space. Previously unseen ulterior motives in my movement began to manifest, particularly during moments of tedium within the exercise. Awareness through movement made me more transparent to myself, revealing my attitudes through movement." (Sandra Reeve) |

Thesis pages

|